It has been said that people either "have it", or they don't in many aspects of life. Some people have innate math and language skills. Others have charisma and people skills. A lucky few have all of the above. These are traits and abilities that we are born with. The Easy Way is no exception. You can't magically make someone who isn't an Easy Way person into one. My dad is a great example. I spent my childhood watching him turn routine household projects into something akin to prison labor.

For example, we once had to move a load of firewood approximately 20 feet. It was stacked in the bed of his pickup. He opened the tailgate, grabbed two or three pieces of wood, walked across the garage and stacked the wood on the floor. He then turned around, climbed back into the bed of the truck and repeated the process. He says "Come on, son, this wood isn't going to unload itself!"

Meanwhile, I am watching this, thinking, "What the heck? We could not possibly make this any harder or slower." My teenage mind was highly motivated to get back to whatever flavor of adolescent summer nothing I was doing before being recruited for firewood duty.

I suggested a bucket brigade: he would stand in the truck bed, hand me a couple pieces of wood; I would then stack it. This went great. We even optimized the process a few minutes later when Dad discovered he could toss me the wood, which eliminated my walking. This worked well until I whiffed on a piece and completely annihilated my big toenail. (TIP: Do not wear sandals when throwing around chunks of oak.) We switched spots and restarted the process soon after my toe quit throbbing.

How does this cute anecdote relate to anything worth reading? By applying a tiny bit of intuition, I created an efficient, labor-saving (nearly zero walking), robust (injury-tolerant) process: the Easy Way.

I believe there is an Easy Way to do almost everything. Signs of the Easy Way:

- Labor is reduced, accelerated, or optimized without an increase in difficulty or effort.

- Tasks are specialized; no one worker completes the entire process chain unless absolutely necessary.

- The Easy Way process has the same beginning and end states as the original Hard Way, thus no changes to the preconditions or outcomes are required.

- The Easy Way process improves on the metrics already used for the original process outcome, such as duration, cycles per day, or fulfilled SLA commitments.

- Interprocess cycle times are typically (but not always) reduced; overall cycle times should be less than or equal to the original process (as required in Bullet #1).

- Preparation steps may add to the overall steps in the process chain, but they must save time and/or effort in a subsequent step.

- Potential risks that would impair or halt the process (injury, subtask failure, etc.) are easily identifiable to both workers and outside observers, and have intuitive solutions which creates built-in robustness.

- It's the Best Way, and it is self-optimizing. You should figure out minor tweaks as you familiarize yourself with the new process. Major changes mean you didn't have the Easy Way the first time.

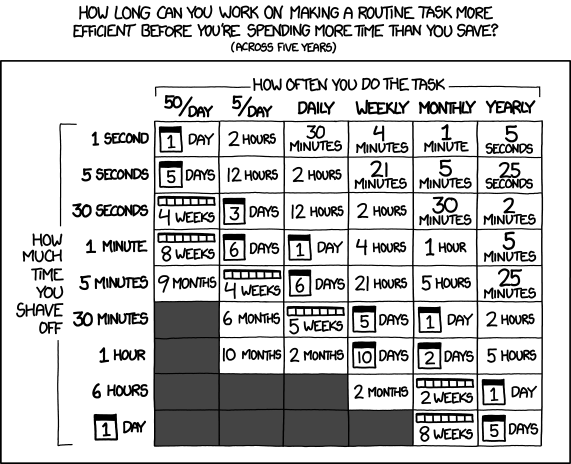

If you need help reading the chart, the upshot is that if you try to save an hour doing your taxes next year, you can't spend more than 5 hours optimizing the process without needing over 5 years to get that time back. On a smaller scale, spend more than a single day's effort to "Easy Way" a single minute out of a daily task, and you will need more than 5 years to recoup the time invested.

Part 2

For me, I hate folding and pairing socks. I have an Easy Way for that. Before I match the first pair, I strip out whites from colors, all-whites from white with logos or gray toes, and so on, placing them into separate work queues. Random matches are paired if I serendipitously find them during the sort. While this increases the overall number of tasks, it significantly decreases the seek time to match a single sock. (This is the part where a programmer will give us a more effective sock-sort algorithm in the comment section.)

Cable techs: When running multiple new drops or outlets, leave the spool at the splitter location and run the cable end to the destination, rather than the reverse. This saves time spent carrying a heavy reel around inside the customer location. For the company, this reduces on-site time as well as potentially lowering medical costs and lost productive days (lifting injuries) and insurance (accidental damage to customer property).

In field service, your Easy Ways should be those that improve the customer experience and/or reduces cost while simultaneously reducing the effort required from technicians and staff. No one has all the Easy Ways in place yet, so keep an eye out around your fleet. Anything that takes more than just a few hours of effort is not the Easy Way. That's a project by definition in many organizations. It might have merit and positive value, but it's not the Easy Way.

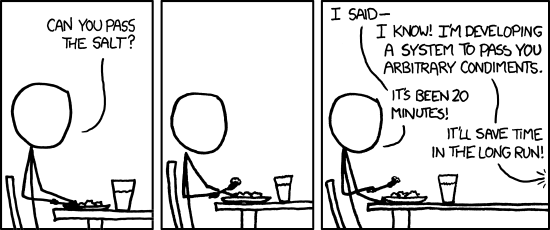

Optimization and automation projects have a tendency to run away from the original estimate, usually because they are poorly scoped and constrained. "Make it better" is not a very good definition of "done". Be careful not to start implementing such a groundbreaking initiative that it becomes all-consuming without a worthwhile return. The Easy Way should never take longer than the original task. That's doing it wrong, doing it the Hard Way (again, courtesy XKCD):

For example, a past employer of mine once invested roughly 12 weeks, 4 full-time IT and operations team members, and unknown dollars into an initiative to save 30 seconds per truck roll for each of our 600 customer-facing cable technicians. At a generous 8 stops a day, this was 20 minutes per tech per week saved at the expense of 1,920 man-hours.

At first blush, this seems excessively wasteful, until you do the math. Assume that IT staff and fleet trucks cost roughly the same to operate per labor hour, which conveniently they do. Close enough for demonstration purposes, anyway (typically more than $30/hour and less than $80):

Input effort:

1920 hours x 60 = 115,200 minutes invested

Output gained:

30 seconds per visit x 8 visits/day/tech = 4 minutes/day/tech

4 minutes/day/tech x 5 days/work week = 20 minutes/tech/week

20 minutes/tech/week x 600 techs = 12,000 minutes/week saved

Payback period:

115,200 minutes invested/12,000 weekly minutes of vehicle operation saved = 9.6 weeks.

This was certainly a worthwhile project. Even if the company was staffed by nothing but sandbagging sandbaggers, and was only completing 4 stops per day per tech, the project would have paid for itself in under 4 months.

This was a classic field service project: drive less if you can; otherwise, don't. We didn't increase our late arrival rate, and saved something like a million dollars in fuel the first year. It was a good cost-cutting project. We saved a significant fraction of the time required for a repeating task. However, as I said before, it was not an Easy Way optimization.

The Easy Way is much subtler, and saves a great deal more time and money with limited upfront cost. Keep your eyes sharp for Easy Way opportunities. They're everywhere. They're often easiest to find in manual work, repetitive "grunt" tasks on the computer, and the household jobs you hate the most. If you are not an Easy Way person by nature, listen very closely to your team member that constantly asks "Why in the world do we do it this way?" If your answer is "Because we've always done it like this", there is likely to be a better, more efficient process: the Easy Way.

No comments:

Post a Comment